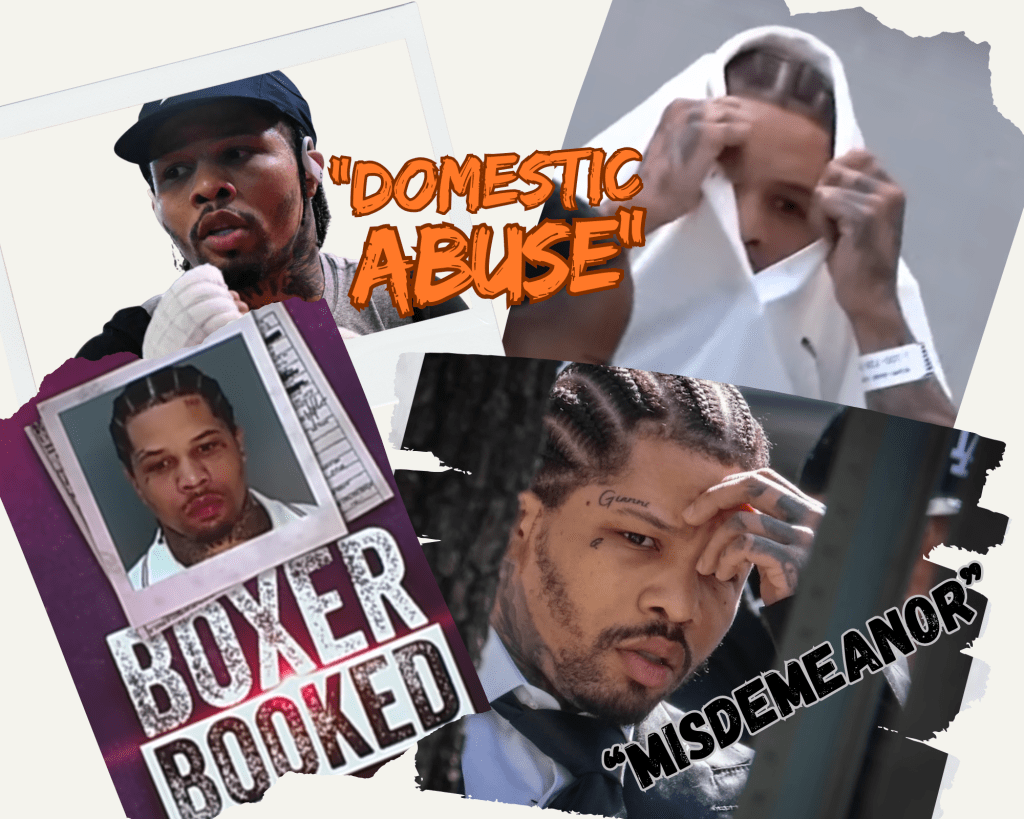

A week after lightweight Gervonta Davis bonded out of jail, there are so many questions reporters through various platforms and fans are asking: “Is the Lamont Davis match still happening? When?” “Did Davis have preferential treatment, as he was escorted by three bondsmen after making bail?”

These questions, along with the articles giving Davis’ behavior a disturbing overtone of “boys will be boys,” is distracting from the real issue at hand: Davis is a repeat offender and an active, conscious participant in domestic abuse and the majority of the media doesn’t know how to handle it. The tentative rescheduling question mark of his fight against Lamont Roach.

The abuse “Tank” Davis perpetrated happened on June 15, when he reportedly went to pick up his children and changed his mind about taking his children with him. When the mother of his two children attempted to remove them from Davis’ car, as Davis instructed her, Davis reportedly “punched her “on the rear of her head with a closed fist and slapped her in the face.”

Davis isn’t new to this style of fight. Domestic abuse, battery incidents can be traced back to 2020. Mark Coppinger of ESPN and Ring Magazine compiled a timeline of Davis’ arrests. This piece was published before the July 11th arrest. ABC Baltimore affiliate WMAR-TV also covered the realities of their hometown lightweight, unbiasedly covering the facts and details of Davis’ past arrests.

This lack of understanding and empathy for victims is not unique to boxing. The MLB, with one of the most recent domestic violence cases manifesting itself twice through Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Julio Urias, the National Football League is culpable of complete forgiveness of star athletes who put their hands on women. Managers and teammates have a real issue with condemning their teammates’ abusive actions post-suspension, but love to have their political, often times discriminatory views heard. In other words, organizations “stand on business” when they feel like it, not when it’s proven that victims were slapped, pushed, or punched at the hands of their fellow athlete.

The opening sentence for the Boxing on S.I. piece, detailing the event was, “Gervonta Davis found himself in hot water again after he was arrested on July 11 in Miami Beach on charges of assaulting his ex-girlfriend.” The same writer, when citing a quote by middleweight champion Bernard Hopkins, wrote the following:

“This is his third case of domestic violence, having previously been arrested for the same in 2020 and 2022. While ‘Tank’ Davis is one of the biggest stars in boxing, he can’t seem to stay out of trouble.”

“Can’t seem to stay out of trouble.” “Found himself in hot water.” These corny, cliche phrases portray a domestic abuser who happens to be a star athlete as someone who participated in teenage, neighborhood vandalism or played with and lost his money after a few days of irresponsible gambling. These phrases minimize the severity of domestic violence and the experiences of victims and survivors. According to a report from the National Institutes of Health and the National Library of Medicine, as of 2023, one in four women are victims of domestic violence.

Bernard Hopkins had some advice for his boxing brethren. Hopkins told Fight Hub TV, “I am not with the domestic violence thing but I hope he can get that straightened out and can get back to focus on his family and his career. Family first, then career second. I just wish both, his ex-girl, his kids’ mother, can get things together and be positive going forward.” As legendary as Hopkins is, this quote shows that to many in the Big Boy Boxing Boxing Brotherhood, domestic violence and being an abuser is something you should just be able to overcome, brush off, and get back to training for the next match up. “Get things together” seems like the child of Davis’ children has culpability in her own abuse and unsolicited victimhood.

Hopkins was also asked whether Davis’ “head is in the wrong place.” Hopkins claimed he doesn’t know ‘Tank’ on a personal level to comment on that. How does it make sense to give advice to an abuser, and also not condemn his actions?

The coverage and verbiage used by sports media YouTube platforms, the questions they ask athletes, the way journalists frame stories regarding domestic violence, sound bites that outlets share from boxing legends are irritating and ignorant. For men who know this sport well, who have trained and drained their blood and sweat, for boxers, defending or having empathy for a repetitive abuser is about brotherhood. For boxing content creators and influencers, it’s about views. For reporters on sports platforms, it is all about who can keep readership most alive without a paywall.

The women who have reported and those who have been silenced under the shadow of athletes, their teams, sponsors, and fans is disheartening. As someone who grew up with and cares for the sport, studied journalism, and survived near-death at the hands of a strong abuser determined to end my life, my heart aches every time domestic violence is swept under the rug to make room for the next cashflow bout in the ring.

If you or someone you know is experiencing domestic violence or the threat of domestic violence, call the National Domestic Violence Hotline for help at 1-800-799-SAFE (7233), or go to www.thehotline.org for anonymous, confidential online chats, available in English and Spanish.

- YWCA Domestic and Sexual Violence Services (national)

- • LA County Domestic Violence Hotline (24/7 Confidential): (800) 978-3600

- • Domestic Violence Shelter 24-hour Hotlines – LA County (download PDF)